PWC, a professional-services firm, reckons that AI could add almost $16trn to global economic output by around 2030 (compared with 2017). McKinsey, a consulting firm, separately arrived at a similar figure, but now reckons this could rise by another 15-40% because of newer forms of AI such as large language models. Yet Africa, which has around 17% of the world’s population, looks likely to get a boost from AI in its annual GDP of just $400m by 2030, or 2.5% of the total, because it lacks digital infrastructure. As a result, instead of helping to narrow the productivity and income gap between Africa and richer countries, AI seems set to widen it.

Take Nigeria, a regional tech hub whose average download speed of wired internet is a tenth of Denmark’s. Most broadband users in Africa’s most populous country are limited to mobile internet, which is slower still. A growing number of underwater cables connect the continent with the wider world, with more to come. These include Meta’s 2Africa, the world’s longest undersea connection. But a dearth of onshore lines to carry data inland will leave much of that capacity wasted.

In some ways Africa’s weak digital infrastructure is explained by the success of its mobile revolution, whereby privately owned telcos entered newly liberalised markets, disrupting and displacing the incumbent operators. These not-so-new firms are still growing rapidly—the 15 main ones have averaged 29% revenue growth over the past five years. But their jump over landlines is coming back to bite them. In much of the rich world, the basic infrastructure of telephones—junction boxes and telephone poles or underground cable conduits—have been repurposed to provide fast fibre-optic broadband. Yet Africa is often starting from scratch.

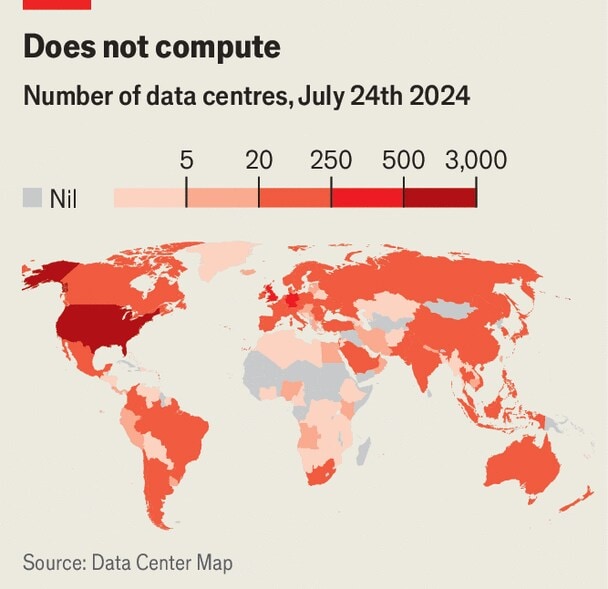

The lack of connectivity is compounded by a shortage of the heavy-duty data centres needed to crunch the masses of data required to train large language models and run the AI-powered applications that could boost Africa’s economic growth. These days much of the content and processing needed to keep websites and programmes running is held in the cloud, which is made up of thousands of processors in physical data centres. Yet Africa has far fewer of these than any other major continent (see map).

View Full Image

Without nearby data centres, bits and bytes have to make long round-trips to centres in cities such as Marseille or Amsterdam for processing, leading to lagging applications and frustrating efforts to stream high-definition films. Yet the closer data are to users, the faster they can reach them: films can zip across to viewers from one of Netflix’s African servers more quickly than you can say “Bridgerton”. The more cable landings and more local data centres there are on the continent, the more resilient its network is if undersea cables are damaged, as happened earlier this year when internet access was disrupted across much of west Africa.

All these new data centres will require more energy as they grow. AI, which involves complex calculations that need even more computing power, will further raise demand. A rack of servers needed for AI can use up to 14 times more electricity than a rack of normal servers. They also need industrial air-conditioning, which guzzles massive amounts of power and water—even more so in ever-hotter climates.

Yet Africa is so short of electricity that some 600m of its people have no power. In Nigeria, which suffers 4,600 hours of blackouts a year, data centres are forced to provide their own natural gas-powered generating plants to keep the lights on and the servers humming. Though many centres across the continent are turning to renewables, wind and solar are too erratic to do the job continuously.

Edge computing, where more data is processed on the user’s device, is promoted as a way to bring AI-powered tech to more Africans. But it relies on the presence of many smaller and less energy-efficient data centres, and on users having smartphones powerful enough to handle the calculations. Though around half of mobile phones in Africa are now smartphones, most are cheap devices that lack the processing power for edge computing.

In 18 of the 41 African countries surveyed by the International Telecommunication Union, a minimal mobile-data package costs more than 5% of average incomes, making them unaffordable for many. This may explain why almost six in ten Africans lack a mobile phone, and why it is not profitable for telcos to build phone towers in many rural areas. “Approximately 60% of our population, representing about 560m people, have access to a 4G or a 3G signal next to their doorstep, and they’ve never gone online,” says Angela Wamola of GSMA, an advocacy group for mobile operators. Every next yet-to-be-connected African is more expensive to reach than the last, and brings fewer returns, too. And new phone towers in remote areas, which typically cost $150,000 each, still need costly cables to “backhaul” data.

Part of the solution to Africa’s connectivity problem may be partnerships between mobile-phone operators and development institutions. Existing telcos know the terrain and the politics that can make laying cables a delicate task. International tech firms such as Google or Microsoft are well placed to take on more risk by laying their own cables and building data centres. Equipment-providers and other multinationals can fill skill gaps.

China’s Huawei, for example, is building 70% of Africa’s 4G networks. Startups using cheaper technologies are exploring how to help far-flung communities get connected. Africa’s connectivity mix will probably be as diverse as its people, including everything from satellites that can be put up by firms like Starlink to reach rural areas, to improved 4G networks in medium-sized cities.

Some foreign firms are investing in data centres in Kenya and Nigeria, but not enough of them. There is also some experimenting with how to power them. Kenya’s Ecocloud Data Centre, for example, will be the continent’s first to be fully run on geothermal energy, a stable source of renewable power. Since Kenya’s grid has plenty more green energy available, it is an attractive place to build more data centres.

But given how many power sources your correspondent switched between to write this article, and how many patchy internet connections interrupted her work, much still needs to be done to improve infrastructure. That is even truer if Africa’s animators, weather forecasters, quantum physicists and computer scientists are to fulfil their potential. Even small-scale farming, which provides a living for more than half the continent’s people, stands to benefit from improved access to AI.

Frustratingly, the case for improving Africa’s digital infrastructure is not new. “Gosh! I can’t believe, 15 years later, we’re still having this conversation,” says Funke Opeke, whose firm, MainOne, built Nigeria’s first privately owned submarine cable in 2010. Unless big investments are made soon, the same conversation may be taking place another 15 years on.

© 2024, The Economist Newspaper Ltd. All rights reserved.

From The Economist, published under licence. The original content can be found on www.economist.com